Biography

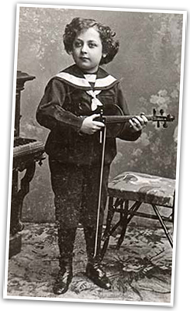

Jascha Heifetz, widely regarded as one of the greatest performing artists of all time, was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, which was then occupied by Russia, on February 2, 1901.. He began playing the violin at the age of two. He took his first lessons from his father Ruvin, and entered the local music school in Vilna at the age of five where he studied with Ilya Malkin. He made his first public appearance in a student recital there in December 1906, and made his formal public debut at the age of eight in the nearby city of Kaunas (then known as Kovno, Lithuania). With only brief sabbaticals, he performed in public for the next 65 years, establishing an unparalleled standard to which violinists around the world still aspire.

Heifetz entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1910. He studied first with I.R. Nalbandian, and then entered the class of Leopold Auer in 1911. By then his public performances were already creating a sensation. One outdoor concert in Odessa in the summer of 1911 reportedly drew as many as 8,000 people. The young Nathan Milstein, who was in the audience, recalled that the police surrounded the boy when he finished playing to protect him from the surging crowd.

In 1912, Heifetz appeared for the first time in Berlin, which was then one of the great musical centers of the world. “He is only eleven years old,” Auer wrote in his letter of introduction to the German manager Herman Fernow, “but I assure you that this little boy is already a great violinist. I marvel at his genius, and I expect him to become world-famous and make a great career. In all my fifty years of violin teaching, I have never known such precocity.”[1]

Heifetz’s Berlin debut took place at a private press matinee on May 20, 1912, at the home of Arthur Abell, the Berlin critic for American magazine, Musical Courier. Heifetz played the Mendelssohn concerto with Marcel van Gool at the piano. Critics and many of the leading violinists of the day attended, including Carl Flesch, Hugo Heerman, Willy Hess, and Heifetz’s idol, Fritz Kreisler. “You should have seen the amazement on their faces,” Fernow gleefully reported to Auer, and “when Fritz Kreisler sat down at the piano and accompanied Jascha in his Schön Rosmarin pandemonium broke loose in the room.” After hearing Heifetz play, Kreisler reportedly turned to his fellow violinists and said, “We might as well take our fiddles and smash them across our knees.”

Heifetz’s public debut in Berlin took place four days later at the large hall of the Hochschule für Musik. A sold out audience packed the 1,600 seat hall. Fernow wrote to Auer that the recital was “a sensational success” and that “the public was wild with enthusiasm.” Then, on October 28, 1912, Heifetz replaced the ailing cellist Pablo Casals to make his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic playing the Tchaikovsky concerto under the direction of the legendary conductor Arthur Nikisch. Years later, Arthur Abell wrote: “When Jascha finished playing there occurred a demonstration such as I have seldom witnessed in more than seventy years of attending concerts. Nikisch himself led the applause and the whole orchestra joined in.”

Heifetz also made debuts in Warsaw and Prague in 1912. He was to have made his American debut in 1914, but the outbreak of World War I precluded travel. Finally, in the wake of the first stage of the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Heifetz family made an arduous journey to the United States. They travelled by way of the Trans-Siberian Railroad from St. Petersburg to Japan. From there they set sail for the United States, crossing the Pacific Ocean with a stop in Hawaii, and landing in San Francisco. They then travelled the length of the United States by train, and finally arrived in New York at the end of August. Heifetz spent most of the next two months preparing for his U.S. debut, which took place at Carnegie Hall on October 27, 1917, with André Benoist at the piano.

That recital stands as one of the most sensational debuts in musical history. The reviews in the many daily newspapers that then existed in New York were so rapturous in their praise that Heifetz’s manager simply reprinted them in their entirety in multi-page ads in the leading music magazines. Musical America hailed the 16-year-old as a “transcendentally great violinist” in a full page review entitled “Hats Off, Gentlemen, A Genius!” Sigmund Spaeth in The Evening Mail said that until Heifetz, the concept of the perfect violinist had just been an ideal. “Then,” he wrote, “a tall Russian boy with a mop of curly hair walked out on the stage of Carnegie Hall and made the ideal a reality.”

William J. Henderson wrote in The New York Sun that Heifetz had the “technique which must make him the admiration and the despair of all the other violinists,” but added that “better than this is the exquisite finish, elasticity and resource of his bowing, which gives him a supreme command of all the tonal nuances essential to style and interpretation.” Pierre V.R. Key added in The New York World that Heifetz’s “breadth, poise, and perfect regard for the turn of a phrase constantly left his hearers spellbound. Nothing that he undertook was without a finish so complete, so carefully considered and worked out, that its betterment did not seem possible….For the moment it is sufficient to say that he is supreme; a master, though only [sixteen], whose equal this generation will probably never meet again.”

Among the many violinists who packed Carnegie Hall that afternoon to hear Heifetz were Fritz Kreisler, Maud Powell, Franz Kneisel, and David Mannes. The one everyone remembers, however, is Mischa Elman—the first great violin prodigy to emerge from Auer’s tutelage. Elman had already been playing in the United States since 1908 and, until Heifetz set foot on the stage of Carnegie Hall, he was widely considered to be Auer’s greatest pupil. Seated next to him at Heifetz’s debut was the pianist Leopold Godowsky. As the first half of the recital progressed, Elman leaned over to Godowsky and whispered: “It’s awfully hot in here.” Without missing a beat, Godowsky replied: “Not for pianists.” To Elman’s everlasting despair, a reporter overheard Godowsky recounting the exchange during intermission, and the story was soon repeated in press accounts around the world.

Two weeks after his Carnegie Hall debut, Heifetz travelled to Camden, New Jersey to make his first recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company. He had already recorded a few sides for the Russian company Zvukopis in St. Petersburg in May 1911, and a few homemade cylinder recordings have survived from a session at the home of Julius Block in Berlin in November 1912, but the Victor recordings mark the true beginning of Heifetz’s recording career. Over the next 55 years, he made hundreds of recordings for RCA Victor and its English affiliate HMV. All of them remain in print, inspiring generations of new listeners.

After extensive tours throughout the United States in 1918 and 1919, Heifetz—long before the ease of air travel—began a series of tours to the far reaches of the world. He became one of the first musicians to be well known through recordings before appearing in person. By the time he made his London debut in 1920, Britons had already bought some 70,000 copies of his records. In the coming decade he toured Europe, India, the Middle East, Australia, Japan, China, and North and South America, taking audiences and critics by storm wherever he went. An avid amateur photographer, Heifetz documented these early travels with home movies. He returned to Russia for the first and only time in 1934, giving concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg, where his boyhood teacher, Nalbandian, stood at the back of the auditorium with tears streaming down his face.

In May 1925, Heifetz became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He was an outstanding pianist, and he celebrated by improvising jazz on the piano at a party hosted by the soprano Alma Gluck and her husband, the violinist Efrem Zimbalist. By then, Heifetz’s fame had already transcended the world of classical music. In the coming years, the name “Heifetz” became so iconic that it was used in radio, motion picture, and television dialogue as a synonym for perfection. Much to Heifetz’s amusement, even cartoons referred to him. He often clipped them and taped them to his filing cabinet in his studio. One, from Parade magazine, showed an irate customer complaining to his mechanic: “$120.34 for a tune up? Who tuned it, Jascha Heifetz?” Another depicted a man mixing a cocktail, with the caption: “Master of mixology: Hei-fizz.”

In 1939, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer built a Hollywood movie, “They Shall Have Music,” around Heifetz. In it, Heifetz—playing himself—came to the rescue of a music school for children by playing an impromptu benefit concert. The fictional school in the movie was loosely based on the Chatham Square Music School in New York. In real life, Heifetz had joined forces to raise money for that school—at a benefit concert he participated in skits and, wearing short pants and a sailor shirt, played in a “student” orchestra conducted by Arturo Toscanini. His fellow students included the likes of Nathan Milstein, Adolf Busch, Josef Gingold, Oscar Shumsky, William Primrose, and Emanuel Feuermann.

Heifetz performed in benefit concerts throughout his career. A “Victory Loan” concert that he gave at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York with pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff in April 1919 raised an incredible $7,816,000 to help pay for expenses incurred by the U.S. government during World War I.[2] When, in 1933, the Great Depression threatened to close the Metropolitan Opera House, Heifetz returned to participate in a benefit to save the Met. Dressed as Johann Strauss, Jr., he took the podium to conduct the “Tales from Vienna Woods Waltz.” During World War II he gave concerts to raise money for U.S. War Bonds and for organizations such as the Red Cross, British War Relief, and the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund. His many benefit concerts in France led the French government to make him an officer in the French Legion of Honor in 1939, a rank that the President of France elevated to commander in 1957. And, his last recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles in October 1972 was a benefit for the Scholarship Fund at the University of Southern California’s School of Music.

Heifetz donated his services to the USO during the Second World War, playing for thousands of service men and women around the world—often in dangerous situations. He played for Allied troops in Central and South America in 1943, in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy in 1944, and France and Germany in 1945. He gave concerts in and near war zones in hospital wards, sports arenas, and often from the back of a flatbed truck that carried around a camouflaged upright piano for his accompanist. One outdoor concert that he gave in Italy in 1944 was bombed, and he briefly found himself lost behind enemy lines in Germany in 1945.

Heifetz had close associations with composers throughout his life. At the age of thirteen he performed the Glazounov concerto under the direction of the composer, who was then the Director of the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Heifetz was an early champion of the Elgar concerto. He studied it with Auer shortly after its 1910 premiere by Kreisler, and performed it in London in 1920 with Elgar in the audience. Sergei Prokofiev was a student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory when Heifetz was there, and heard Heifetz play with Glazounov. Years later, Heifetz championed Prokofiev’s second violin concerto, giving its U.S. premiere in 1937, and making the first recording of it shortly thereafter.

Heifetz also commissioned and premiered concertos by William Walton, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Miklós Rózsa, Louis Gruenberg, and Erich Korngold. He met Shostakovich when he returned to Russia in 1934, knew Stravinsky and Schoenberg, made an effort to program music by contemporary American composers on his recital programs, and had ties with Darius Milhaud, Ernest Bloch, and others. He met Sibelius in Finland and helped to popularize his concerto, making its world premiere recording.

Heifetz was a composer himself. He contributed significantly to the violin repertoire by creating dozens of masterful transcriptions and arrangements of works by other composers. He published his first transcription, of Ponce’s Estrellita, in 1928. Two years later he created a sensation with his arrangement of Dinicu’s Hora Staccato. Heifetz was a close friend of George Gershwin, and he asked him to write something for the violin. Gershwin died before he could honor the request. Heifetz helped to make up for that loss by transcribing Gershwin’s three piano preludes in 1942 and songs from Porgy and Bess in 1944. They are now among the most beloved transcriptions in the violin repertoire.

In the 1940s, Heifetz—under the pseudonym Jim Hoyl—wrote several popular songs with the lyricist Marjorie Goetschius. One, When You Make Love to Me (Don’t Make Believe), became a hit in 1946. Among those who recorded it were Bing Crosby, Dick Jurgens, Helen Ward, and Margaret Whiting, and the song was featured in the soundtrack to the 1949 movie, The Set-Up, directed by Robert Wise and starring Robert Ryan.

In the 1950s, Heifetz returned to Europe, Japan, and Israel where, in 1953, he was attacked by a man wielding a metal pipe for playing the violin sonata by the German composer Richard Strauss. He also continued to tour the United States and, in December 1959, he played at the United Nations in New York. The previous year he began teaching at the University of California at Los Angles. Leopold Auer once “put a finger on me,” Heifetz told a reporter at the time. “He said that some day I would be good enough to teach.” Heifetz moved to the University of Southern California in 1962 where several of his masterclasses were filmed and broadcast on television. He continued to teach at USC until 1983. “Violin playing is a perishable art,” Heifetz said. “It must be passed on as a personal skill—otherwise it is lost.”

Heifetz had a long love of chamber music. He played it privately with friends throughout his life, and as early as 1934 performed Beethoven’s op. 127 string quartet publicly at a benefit concert at New York’s Town Hall for the Beethoven Association. He made legendary chamber music recordings with violist William Primrose, cellist Emanuel Feuermann, and pianist Arthur Rubinstein in the 1940s. After the untimely death of Feuermann in 1942, Heifetz formed a trio with Rubinstein and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. They appeared in a series of four concerts at the Ravinia Festival just outside of Chicago in the summer of 1949, made a series of recordings, and were featured in a film. Critics quickly dubbed them the “Million Dollar Trio.”

Heifetz and Piatigorsky had planned another series of trio recordings with the pianist William Kapell in the 1950s, but Kapell’s death in a plane crash in 1953 prevented that. Then, in 1961, they began a series of “Heifetz-Piatigorsky Concerts.” In the coming years they traversed a wide range of repertoire with fellow musicians, from duos by Toch and Kodály to octets by Mendelssohn and Spohr. They gave concerts in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, and made many recordings.

Heifetz’s solo performances became rarer in the 1960s, but he returned to England to record concertos in both 1961 and 1962, and gave concerts in Israel in 1970. He performed the Beethoven concerto at the opening of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles in 1964, gave solo recitals in New York in 1966 and Los Angeles in 1968, and filmed a concert for television in Paris in 1970 that aired in the United States on NBC in 1971. His last recital took place in Los Angeles in October 1972, 55 years after his U.S. debut. He continued to perform in concerts given by his students at the University of Southern California until 1974, when a shoulder injury put an end to his public career.

Heifetz championed a number of causes throughout his life. He was active in unions, serving as a founding member and first vice president of the American Guild of Musical Artists in 1936 and as a founding member of the American Federation of Radio Artists in 1937. Later, he led efforts to establish “911” as an emergency phone number, and crusaded for clean air. He and his students at the University of Southern California protested smog by wearing gas masks, and in 1967 he converted his Renault passenger car into an electric vehicle.

Heifetz was married twice, to Florence Vidor from 1928 to 1946, and to Frances Spiegelberg from 1947 to 1963. Both marriages ended in divorce. He had two children, Josefa and Robert, with his first wife, and one, Jay, with his second. Heifetz was an avid sailor, loved ping pong and tennis, and collected books and stamps. He died on December 10, 1987 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, but his magic lives on through his recordings, which remind us why the great critic Deems Taylor once wrote that Heifetz has “only one rival, one violinist whom he is trying to beat: Jascha Heifetz.”

by John and John Anthony Maltese

John Maltese was professor emeritus of music at Jacksonville State University, Alabama. John Anthony Maltese is the Albert B. Saye Professor and Head of the Political Science Department at the University of Georgia, and he is currently writing the authorized biography of Jascha Heifetz.

This biography may be used in whole or in part as long as the following credit accompanies it: “From the Jascha Heifetz Biography at www.JaschaHeifetz.com, © 2010 John and John Anthony Maltese”

[1] The correspondence between Auer and Fernow, as translated from the German by Arthur M. Abell, was printed in: Arthur M. Abell, “When Heifetz, Aged 11, Stormed Musical Berlin,” Musical Courier, May 15, 1952, pp. 6-7. The other quotes, including Abell’s description of Heifetz’s debut with the Berlin Philharmonic, are from this same source.

[2] “Huge Sum in Notes Earned by Encores,” New York Times, April 29, 1919.