Jascha Heifetz: Violinist Nonpareil

by John and John Anthony Maltese

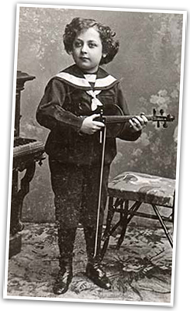

The triumphs of Jascha Heifetz are well known: first public performance in his hometown of Vilnius, Lithuania (then occupied by Russia) at the age of 5; Berlin Philharmonic debut at the age of 11; one of the most memorable debuts in the annals of Carnegie Hall at the age of 16; followed by tours, long before the ease of air travel, to the far reaches of the world: Japan, Australia, South America, India, the Middle East, and beyond—conquering audiences wherever he went. In all, he had a public career lasting some 65 years.

Heifetz was already “Heifetz” from a startlingly early age. Sascha Lasserson, who studied violin alongside the young Jascha in Leopold Auer’s fabled class at the St. Petersburg Conservatory was asked years later what Heifetz’s playing was like as a child. Lasserson thought for a moment and said simply, “He hasn’t improved a bit.”

Fritz Kreisler—Heifetz’s idol—heard the 11-year-old Jascha play the Mendelssohn concerto and then accompanied him at the piano in his own Schön Rosmarin at a private concert in Berlin in April 1912. When Heifetz finished, Kreisler famously turned to the other violinists present and said, “We might as well take our fiddles and smash them across our knees.” Primitive home recordings of Heifetz made in Berlin a few months later prove that the accolades of critics and fellow violinists were not mere hyperbole.

Kreisler’s admiration of Heifetz never waned—nor did Heifetz’s admiration of Kreisler. The two often attended each other’s concerts. At one such Carnegie Hall recital in March 1953, Heifetz played Kreisler’s Recitativo and Scherzo in honor of the aging composer who sat in the second row. When he finished playing, Heifetz motioned for Kreisler to stand, to thunderous applause.

In his final years, Heifetz kept a signed Kreisler program on the wall of his studio at the University of Southern California. Daniel Mason, one of Heifetz’s students, told us that Heifetz made it clear that Kreisler was still his big love. “He didn’t play Kreisler’s pieces much in public, out of respect to Kreisler,” Mason said, “but he played them often in class. And when he played them in class he imitated Kreisler perfectly. He could sound exactly like Kreisler.”

Even Kreisler was once fooled by Heifetz’s playing of one of his own compositions. At a tribute held for Kreisler by fellow musicians in 1940, the great American violinist Albert Spalding dressed up like Kreisler. He put soap on his bow so that it wouldn’t sound when he drew it across the strings. Behind a curtain Heifetz played one of Kreisler’s compositions while Spalding pretended to be Kreisler performing. Afterwards, Kreisler went up to Spalding and, assuming it was a phonograph behind the curtain instead of Heifetz, said, “It was so nice to hear one of my old records!” Heifetz beamed when he heard what Kreisler said. Years later, Heifetz recounted the story to his students, and Daniel Mason said it was the only time he could recall when Heifetz seemed genuinely proud of his own playing.

Heifetz also had a talent for a different type of mimicry. Another one of his pupils, Elaine Skorodin, recalls a dinner party she attended at Heifetz’s home. Before dinner, he announced that he and his accompanist, Brooks Smith, wanted to play a short recital. The guests were pleasantly surprised and took their seats in his studio. But when Heifetz started to play, everyone froze. His rhythm and intonation were off. How could this be? Heifetz’s face was expressionless, as usual, but he was looking at his guests out of the corner of his eye and, despite a gallant effort, Brooks Smith could not contain a smile. Heifetz was engaging in one of his old party tricks: imitating, perfectly, a bad student.

Of course, Heifetz’s own sound on the violin was entirely unique. He played with gut D and A strings, but produced an intense tone with a fingertip vibrato that he would adjust to create impeccable nuances. His technique was, to put it mildly, amazing, but he was no mere technician. Instead, he used his technique to further his art. It gave him the flexibility to sculpt every phrase, no matter its difficulty. His tonal palette was vast, and always perfectly coordinated and controlled.

Heifetz believed that any obstacle on the violin could be overcome. If his students’ strings went out of tune while they were playing, he would not allow them to stop and re-tune the violin. One time, when a student complained that it was impossible to continue under such conditions, Heifetz picked up his violin, put it radically out tune, and proceeded to play Paganini’s 16th caprice flawlessly. When he had to substitute a finger for a note that would ordinarily have been an open string, he did it automatically and perfectly. The entire class was dumbfounded.

Daniel Mason, who witnessed that feat, came away convinced that there was absolutely no physical barrier between what Heifetz heard in his head and what he was able to produce on the violin. On another occasion, a student was playing the Schubert A major Duo on a violin that was badly out of adjustment. A difficult octave passage in the slow movement proved to be problematic on the instrument. Heifetz took the violin and, uncharacteristically, also had trouble in the octave passage. He made a face and was just about to say something, when Grant Beglarian, the Dean of the University of Southern California’s School of Music, unexpectedly walked into the studio for a ceremonial visit.

After introductions and pleasantries, Heifetz said, “Where were we?” He still had the student’s violin in his hands. All the students waited to see what he would do. He could have simply returned the violin, but by doing so he would have lost face in front of the students. So he stepped up to the moment. He put the violin back under his chin and did the only thing he could do under the circumstances: he played the passage perfectly despite the limitations of the violin. Beglarian was oblivious to the significance of this, but it made a strong impression on the class. Heifetz handed back the violin and said simply, “Mind over matter.”

Though Heifetz is known best as a violinist, he also had an extraordinary talent for the art of arranging and transcribing works for the violin. He transformed everything from keyboard works by Chopin and Poulenc to songs by Ponce and Gershwin into little masterpieces that sounded like they were meant to be played on the violin. One, Hora Staccato, transcended the world of classical music and became a bona fide sensation. Many of these transcriptions can be heard in this set and have entered the standard repertoire of today’s violinists.

Heifetz could also improvise beautifully. One time while teaching he asked the class pianist to play the accompaniment to the Mendelssohn concerto. He then proceeded to make up an entirely new violin part on the spot. His original compositions were limited to popular songs written under the pseudonym Jim Hoyl. One, “When You Make Love to Me (Don’t Make Believe),” became a hit in 1946. Among those who recorded it were Bing Crosby, Helen Ward, and Margaret Whiting. Once the song had made it on its own, Heifetz confessed to writing it.

Over the years, Jim Hoyl became something of an alter ego to Jascha Heifetz. The name Heifetz was a difficult one to live up to. As “Heifetz,” he was a legend: on display, judged, unable to let down his guard. At the height of his career, Heifetz was a household name—one synonymous with perfection. For this shy and intensely private man, being Heifetz must have been a difficult burden. And so “Jim Hoyl” became the antithesis of “Jascha Heifetz”: relaxed, anonymous, tin pan alley. Heifetz’s fishing licenses bear the name Jim Hoyl, and at parties—when he really let his hair down—Heifetz asked others to call him Jim.

A story recounted by Daniel Mason is a revealing and moving one. In 1976, the University of Southern California wanted to celebrate Heifetz’s 75th birthday with a gala event. Characteristically, Heifetz refused. He did not like public celebrations of birthdays and anniversaries, and he shunned tributes. When his manager, Arthur Judson, suggested a silver anniversary commemoration of his 1917 U.S. debut, Heifetz refused. Late in life he also refused to be honored by the President of the United States at the annual Kennedy Center Honors in Washington, D.C.

Aware of all this, Heifetz’s students nonetheless wanted to celebrate his birthday. So, they decided to hold a surprise birthday party for him in class. They knew that hijacking class for such a purpose was perilous, but they came up with an idea that they thought Heifetz might like. He always insisted that in order to be good all-around musicians, his students must be able to play another instrument beside the violin. Thus, he required them all to take piano lessons and to accompany one of the other students in class once a semester (Heifetz, himself, was a very accomplished pianist).

So, the students decided that they would surprise Heifetz with a performance of a tango. But, they would all play instruments that they really didn’t know how to play. The result was a very dismal sounding ensemble, but one that they hoped Heifetz would appreciate. In order to execute the surprise, they had to enter Heifetz’s studio at USC before he arrived—something they had never done before. The plan was for them to start to play as soon as he entered the room. When finished they would serve cake and other food and refreshments to their surprised teacher.

On the day of the surprise, the students were terrified. No one knew how Heifetz would react. When he walked into the studio, the students launched into a performance of their rag-tag tango. Heifetz was carrying his violin case in one hand, a black bag in the other, and he wore a hat. At first he just stood in the middle of the room and didn’t move. More nervous than ever, the students pushed onward with their tango, glancing to see what Heifetz would do. Very slowly, he put down his violin case, and then very slowly he put down his bag. With a grand gesture he lifted off his hat and, in a magical moment, began a solo dance around the room.

“It was magical because we knew the joke was okay with him, but also because he was a great dancer, so it was really beautiful to watch him,” Mason told us. When they finished playing, the students rushed to the next room and brought in the cake and began to sing, “Happy Birthday, Mr. Heifetz”—it was always Mister Heifetz. But he quickly interrupted them: “You’ve got the wrong guy,” he said. “You don’t want me. You want a friend of mine. I think he’s nearby. I’ll go get him.” He then left the room as Jascha Heifetz and returned a few seconds later as Jim Hoyl. “He said ‘Jim’s here,’ and then we were calling him Jim, and he was a totally different persona.”

Heifetz’s reserve has often been mistaken for coldness, or worse. He was formal. He was a man of few words, highly organized, deeply patriotic, and extraordinarily disciplined. Immaculate in everything he did, he expected the same from those around him. But, in the end, he was more demanding of himself than of anyone else.

When the pianist Milton Kaye auditioned to be his accompanist in 1944, Heifetz warned him that he expected only the best from him. “If you are an artist, you do things correctly,” Heifetz explained. “Not half way – fully.” He paused and looked at Kaye. “Do you want to be an artist?” he asked. Kaye nodded. “Then no approximation,” Heifetz said. The blood must have drained from Kaye’s face, because Heifetz then offered some revealing words of comfort: “If you think I am tough on you, remember, I am twice as tough on myself.”

Beneath Heifetz’s formal exterior was a boyish sense of humor. He loved games and parties. Especially in his early years he would participate in elaborate skits—often written by his brother-in-law and one-time accompanist, Samuel Chotzinoff. The pianist Jacob Lateiner, who collaborated in chamber music concerts with Heifetz and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky in the 1960s, and who can be heard in several of the chamber music recordings in this set, later wrote that Heifetz was “probably the best host I have ever met in my life.”

Lateiner would rehearse daily with Heifetz and Piatigorsky from 10:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. with a break for lunch. Heifetz never dominated the rehearsals, according to Lateiner, but they worked very hard. “Our preparation was such that by the time we got to the performance there was room for spontaneity.” This preparation reflected a maxim that Heifetz passed on to his students: “Practice like it means everything in the world to you. Perform like you don’t give a damn.”

Leonard Pennario, another pianist who participated in chamber music concerts and recordings had similar recollections of Heifetz as both host and collaborator. He said that he learned more from Heifetz during their rehearsals than from any teacher he ever had, and he spoke of the great camaraderie fostered by Heifetz when they played together. Interspersed between the hours of rehearsals were meals, afternoon swims, and games of ping pong and gin rummy.

Heifetz was generous with others in ways that often defy common wisdom. For example, he quietly gave fine violins and bows to his students, helped them with rent money, and insisted on visiting each of them at their own home—but always with the understanding that they not talk about it to others. Late in life, these students became a second family to Heifetz. He invited them several times a year to his home in Beverly Hills or his beach house in Malibu. Thanksgiving at the beach became a time-honored tradition. Erick Friedman, with whom Heifetz recorded the Bach double concerto, once said that “Heifetz’s consideration and tact for others he cares about is beyond most people’s imagination.”

Heifetz gave his last public recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles on October 23, 1972—a benefit concert that was recorded and is included in this set. We were both in the audience. Just ahead of us, tears streamed down the face of an elderly woman as Heifetz played the slow movement of the Strauss sonata, and just down the row from us sat the great comedian and better-than-he-let-on violinist Jack Benny, who was a longtime admirer of Heifetz. Together the two had performed a comedy skit and a duet for U.S. troops during World War II—part of Heifetz’s tireless (and often dangerous) service for the USO during the war.

No one knew this would be Heifetz’s last recital, but Brooks Smith later said that he sensed it. Heifetz was very tired. He played only one short encore, Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Sea Murmers, and gave a brief curtain speech. Saying he was “pretty much poop-ed,” he apologized for not being able to attend a post-concert party. He then retreated to his dressing room and, uncharacteristically, refused to see anyone. It was the end of his formal public career.

Heifetz continued to teach and made his last, unannounced, public performance at a student concert on the campus of the University of Southern California on April 28, 1974. Piatigorsky’s pupils were scheduled to play the Bachianis Brasileiras No. 5 for cellos and soprano by Hector Villa-Lobos. At another concert not long before that one, Beverly Sills had sung the soprano part with them. This time, Piatigorsky strode on stage to introduce the work. “We can’t have Miss Sills today,” he told the audience, “so we’ve looked within our own family and have found a very talented boy soprano. We won’t have cleavage or décolletage, but we will have talent.” With that, Heifetz walked on stage and performed the soprano solo on the violin. He played the entire piece on one string, using just one finger on his left hand to imitate the sound of a human voice.

Not long afterwards, the muscles in Heifetz’s right shoulder hemorrhaged. Surgery and physical therapy did not repair the damage, leaving him unable to raise his right arm. Nonetheless, he still managed to play in class, tilting and contorting the violin in order to accommodate the limitations of his arm. If he wanted to play on the G string he would sometimes ask a student to hold up his arm. In that condition, he played the entire Tchaikovsky piano trio in class. It was yet another example of “mind over matter.”

Luckily, we have a vast collection of recorded performances of Heifetz chronicling almost his entire career—from his first recordings made in St. Petersburg at the age of 10, to his final recordings made late in his 71st year. Included in this set are several concertos that Heifetz commissioned: the Korngold, Walton, Rózsa, Gruenberg, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco 2nd, as well as world premiere recordings of concertos he championed, such as the Sibelius and Prokofiev 2nd.

As a boy, Heifetz performed the Glazounov concerto with the composer conducting, and he was an early champion of the Elgar concerto—learning it under Auer’s tutelage shortly after its premiere and meeting Elgar in 1920. You can hear both, as well as the sonatas of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, lesser-known ones by Bloch, Ferguson, and Karen Khachaturian, and a wealth of chamber music that runs the gamut from Mozart and Schubert to Turina and Toch. Of special interest are several previously unissued studio recordings.

The list of Heifetz’s collaborators on these recordings is a long and distinguished one that can easily be gleaned from the accompanying discography. Less obvious are the extraordinary musicians who performed in the pick-up orchestras billed as the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra. For example, it included such violinists as Sol Babitz, Israel Baker, Anatol Kaminsky, Peter Meremblum, Lou Raderman, Eudice Shapiro (who often served as concertmaster), and Felix Slatkin. None other than Toscha Seidel played in the violin section for such recordings as the Conus and Spohr concertos, Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole, and the 1952 recordings of Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso and Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen.

Seidel, of course, had been one of Auer’s great prodigies, studying in the same class as Heifetz. He and Heifetz had concertized together as boys, playing the Bach double concerto, and Seidel had made a very successful Carnegie Hall debut in 1918, just one year after Heifetz. He was—along with Heifetz, Mischa Elman, and Sascha Jacobsen—the inspiration behind the Gershwin song, “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha.” (Jacobsen led the Musical Art Quartet in Heifetz’s recording of the Chausson concerto for violin, piano, and string quartet.) Seidel eventually abandoned his solo career for a very successful one as a studio musician in Hollywood, thus ending up in the orchestra for Heifetz.

For much of his career, Heifetz had to contend with the claim that his playing was “cold.” The cellist Laurence Lesser, who performed in the recordings of Spohr’s double quartet and Tchaikovsky’s Souvenir de Florence, strongly contests that claim. “He was a hot player,” Lesser insists. “Nobody has ever played with more passion.” Many others agree. Why, then, did the claim stick? No doubt it was partly because people listened with their eyes, and Heifetz’s stage presence was impassive—no swooning, swaying, or smiling.

Before his 1971 television broadcast, Heifetz responded to a question about his stage presence by saying: “Actually, I don’t feel I’m impenetrable, cool or aloof when I’m on the stage. I’m not even aware that I appear serious. If I don’t smile…it’s only because I become so absorbed in my playing that I forget everything else. If a smile doesn’t come spontaneously, why resort to an artificial grimace?”

Listen for yourself, and see if you don’t agree with Howard Taubman, longtime music critic at the New York Times, who once offered a retort to the charge that Heifetz was “a splendid, heartless violin-playing machine” by saying that “anyone with ears to hear” knows this charge is “rubbish.” “For me and many others,” Taubman wrote, “he was a nonpareil of violinists. He had everything—technique in superabundance, purity of tone, taste, loftiness of feeling.” Thanks to his many recordings, generations to come can judge for themselves and bask in the artistry of Jascha Heifetz.

This article appears in Sony Music’s “Jascha Heifetz Complete Album Collection,” and is reproduced here with their permission.

John Maltese was Professor Emeritus of Music, Jacksonville State University, Alabama; his son, John Anthony Maltese, is the Albert B. Sayer Professor and Head of the Department of Political Science at the University of Georgia — a longtime noted authority on Heifetz and his recordings, he is currently writing the first authorized Heifetz biography.